The life story of Hannie Schaft

On April 17, 1945, a few weeks before liberation, Hannie Schaft was executed in the dunes near Overveen and carelessly buried in the sand on the spot. With the end of World War II approaching, the resistance and the occupying forces had agreed not to kill any more hostages. Moreover, the Nazis normally did not execute captured women. But for this “girl with the red hair,” they made an exception.

Armed resistance

The Nazis considered Hannie Schaft a terrorist. This reputation stemmed from her active role in the armed resistance. She was involved in several attacks, including those on Piet Faber and the Zaan police captain Ragut. Ragut was believed to have been employed by the Sicherheitspolizei and had made a substantial profit from betraying people. For a long time, the Sicherheitspolizei was particularly keen to capture this “Murderin.”

Jo Schaft

The seemingly fearless Hannie Schaft was born Jannetje Johanna Schaft, nicknamed Jo, on September 16, 1920, in Haarlem. When Jo was seven, her only sister died of diphtheria. From then on, her parents were constantly worried that they would lose Jo as well.

Classmates—both those at the Tetterode School and those at the HBS-B—describe her as a withdrawn, shy, and somewhat prissy girl who primarily read books and achieved high grades. She had no friends.

From small things we strive for great things

Student days

This changed in 1938, when she began studying law at the University of Amsterdam. Jo joined the Amsterdam Female Student Association (AVSV), survived the hazing, and quickly made friends. She spent a lot of time with Philine Polak and Sonja Frenk, two Jewish students. They studied together, ate together, and went on outings together. With Annie van Calsem and Nellie Luyting, she founded a new society called Gemma (gemmare e minoribus appentinus = from the small things we strive for the great). After the summer of 1940, she and their group rented an attic room on Michelangelostraat in Amsterdam-Zuid.

Socialist values

Jo was raised with values such as solidarity, justice, and equality. Her father was a teacher at the National Teacher Training College and a member of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP), while her mother came from a family of socialist ministers. At the dinner table, Jo participated in discussions about world events. The ideal of a just world led her to study law. She specialized in international law and dreamed of going to Geneva to revitalize the League of Nations.

National Socialism

The Schaft family was aware of the danger of National Socialism from an early stage. They closely followed developments in Germany, and their concern grew when the NSB (Dutch Nazi Party), related to Hitler’s NSDAP (National Socialist Party), won nearly eight percent of the vote in the 1935 provincial elections in the Netherlands. In 1939, the Nazis invaded Poland. Jo was eager to do something to help. For months, she sent parcels to captured Polish officers through the Red Cross. At university, she attended lectures by, among others, Professor Dr. H.J. Pos, founder of the Committee of Vigilance. This committee of intellectuals fought against fascism and the NSB through brochures and lectures. While collecting for refugees from Spain during one of these lectures, Jo met Philine Polak, with whom she became friends. Jo was also horrified by lectures by Professor Dr. L.J. van Apeldoorn, who made no secret of his NSB sympathies during his lectures.

Small resistance

During the occupation and capitulation in May 1940, Jo was at home with her parents in Haarlem. Shortly after the capitulation, Bernard IJzerdraat’s “Geuzenbericht” (Geuzen Report) was published there, calling for resistance. After a few days, Jo returned to Amsterdam to visit Philine and Sonja, but also to study, because despite the occupation, life went on. On July 1st, she passed her bachelor’s degree. Jo talked a lot with her friends about the war. They listened to the illegal radio station Radio Oranje and sometimes took illegal leaflets from the university. Jo’s resistance consisted of deliberately looking the other way when she encountered German soldiers or shrugging her shoulders when they asked for directions. That was all they could do at that moment.

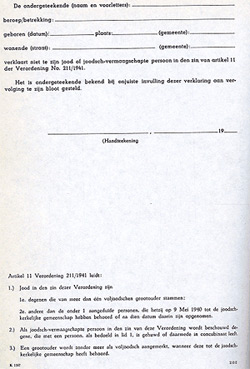

Ariërverklaring

Persecution of Jews

In the autumn of 1940, the persecution of Jews in the Netherlands began with the Aryan Declaration that government employees were forced to sign, followed a month later by the dismissal of Jews. Several professors were also forced to resign. A planned student strike failed to materialize. Only months later, when 400 Jewish men were arrested and deported in raids in Amsterdam, did the first visible resistance emerge in the February Strike (1941).

New measures against Jews followed in the autumn. Parks, public gardens, libraries, theaters, and concert halls were banned. Jo’s response: “If they’re not allowed to go through that park anymore, I won’t go through it either.” Her Jewish friend Sonja replied: “If I’m not allowed to walk through it anymore, I will.” [source] When Jews were also banned from student associations, most student associations—including the AVSV—suspended their activities. The Gemma society continued to meet.

Identity cards for people in hiding

Jo’s first concrete illegal resistance activity was stealing identity cards. This occurred in the spring of 1942, when the Star of David became mandatory and Jews were no longer allowed to cycle or travel by public transport, nor were they allowed to go outside in the evenings and at night. Jo stole identity cards of her peers from a swimming pool locker room and had her fellow student Erna Kropveld forge them for her friends Sonja and Philine.

Major raids in Amsterdam followed shortly thereafter. Along with several other students, Jo helped Philine and Sonja find various hiding places. Jo subsequently stole dozens more identity cards from swimming pools, theaters, concert halls, and cafes. She did this on her own initiative and at Erna Kropveld’s request. If Erna requested it, Jo would provide an identity card of someone with the correct gender and age within hours. She also collected donations and items for deported Jews. Through the Red Cross, she sent parcels to Westerbork and camps in Germany. In her parental home she had set up a small room where she stored things she had collected from neighbours, family and acquaintances.

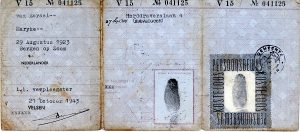

Vervalst persoonsbewijs

Declaration of Loyalty

In early 1943, there were raids on universities following attacks (including the attack on General Seyffardt). On March 13, 1943, it was decreed that every graduate had to work in Germany for a period.

Loyaliteitsverklaring

Moreover, students were only admitted to the university if they signed a loyalty declaration, in which they declared they would comply with the occupier’s regulations and refrain from resistance. In the Gemma dispute, there was almost unanimous agreement that this declaration should not be signed. Ultimately, 85% of students in the Netherlands refused the loyalty declaration. After this, at most, lectures and exams were held clandestinely. Presumably, Jo Schaft also took an exam in the restaurant at Amsterdam Central Station in this way, which she used to complete her law studies. Shortly afterward, Philine and Sonja moved in with her and her parents in Haarlem.

Council of Resistance

In response to the attack on Hendrik Bannink (WA) and a German non-commissioned officer in Haarlem, one hundred Haarlem residents were transported to Vught and ten Haarlem hostages from “Jewish-communist circles” were executed. The occupying forces responded to a strike call from the Resistance Council with extreme repression: more than one hundred people were killed, and nearly a thousand were transported to Vught. In response to such events, Jo tried to contact the resistance, which she finally succeeded in the summer of 1943.

Truus en Freddy Oversteegen

One of Jo’s first assignments was to contact Truus and Freddy Oversteegen, who were in hiding in Twente. From that point on, the trio worked closely together in the resistance. They provided intelligence on German defenses, transported illegal newspapers and weapons, provided false identity papers, and guided people in hiding to new addresses. Jo and Truus regularly went swimming at the Overveen swimming pool to socialize with German soldiers and their lieutenant Willy and extract information from them. They also stole two revolvers. Jo took shooting lessons and, usually in pairs, carried out attacks on various traitors.

Over time, Jo’s entire life was dedicated to the resistance. She was a lookout during the attack on the PEN power plant in Velsen-Noord, smuggled ammunition crates from IJmuiden, and mapped the coastal defenses (Atlantic Wall). She did this through reconnaissance and conversations with Germans. She could get everywhere thanks to a forged Ausweis with stamps.

Jan Bonekamp

Jan Bonekamp

Together with Jan Bonekamp, she attacked Piet Faber in Heemstede and a short time later, the Zaan police captain Ragut. He was believed to be employed by the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) and had made a considerable profit from betraying people. On the Westzijde, Hannie shot him off his bicycle. Jan followed to deliver the coup de grace. But Ragut simultaneously shot Jan in the stomach. Jan fled into a house and ended up at the first aid station, where an officer alerted the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service). In Jan’s final hours, they extracted several addresses from him. Finally, Emil Rühl, claiming to be a friend, leaned over him and asked if he could do anything for him. Jan then gave Hannie Schaft’s address on Van Dortstraat.

Parents held hostage

Jo had just gone into hiding and helped Philine find a new hiding place when the Sicherheitspolizei, accompanied by Emil Rühl, raided her parents’ home. They held her parents hostage, hoping that the red-haired girl, who had been seen in various sabotage operations and assassinations, would then turn herself in. Jo almost did. But Truus and Freddie convinced her that the Nazis wouldn’t let her parents go even if she turned herself in. After a few weeks, her parents were released. Because they were “in the picture,” Jo could only visit them secretly very occasionally.

Jo became Hannie Schaft

Because “the girl with the red hair” had been spotted in several attacks, she dyed her hair black and wore window-glass glasses, making her unrecognizable. She received a new identity card: Johanna Elderkamp, born in Zurich. Identity card 040734, issued on March 8, 1944. From that moment on, she called herself Hannie.

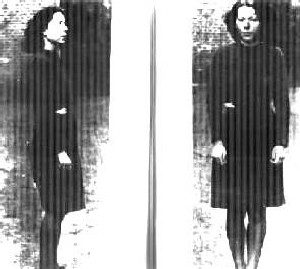

Met vermomming

Less hard than she thought

Jan Bonekamp’s death left Hannie deeply devastated for a while. In a letter to Philine, she wrote that she couldn’t read and was knitting a stocking in her spare time, even though she was definitely not a knitter.

“I’m considerably less hardened than I thought: encountering death hasn’t been easy. (…) I’ll still try to salvage the fragments of my old self. But that’s probably no longer possible. People are in such a festive mood. [Paris and Brussels had already been liberated – H.A.] I’m sitting there like a smiling Buddha, and they expect me to be in a festive mood too. I’d love to swear.”

More resistance

After some time, she, Truus, and Freddie resumed their resistance work, more determined than ever. She carried out attacks on at least eight collaborators. Not all of these attacks were successful; sometimes multiple attempts were made by different resistance groups. Hannie participated in a failed assassination attempt against three leading members of the Haarlem police: Inspector Fake Krist, Willemse, and Smit. The resistance members, including Hannie, were injured, and she had to recuperate at another hiding place. Hannie, Truus, and Freddie refused to carry out actions that victimized innocent people. For example, they refused to kidnap Seyss Inquart’s children.

Hannie Schaft, Truus, and Freddie Oversteegen also carried out various assignments for the Velsen resistance during the Hunger Winter. After some time, they became increasingly suspicious of this resistance group, but they were unsure what was going on. The Velsen Affair only came to light after Hannie’s death.

Truus en Hannie als verliefd stelletje, kort voor een aanslag

Hannie Schaft arrested

In the detention center on Amstelveenseweg, Hannie Schaft was isolated and interrogated for days. It was known that she had committed the attacks on Ragut and Faber. After some time, she also confessed to the attack on Ko Langendijk, thus unknowingly preventing the execution of five female hostages. The resistance attempted to bribe Germans. Oberstrumbannführer Armin Hinkfusz received assurances that Hannie Schaft would not be shot. Agreements had already been made between the occupiers and the resistance that neither would carry out any further assassinations.

Hannie Schaft, kort voor haar executie

Execution

Nevertheless, Willy Lages of the Sicherheitspolizei gave the order for her execution. On April 17, 1945, Hannie Schaft was taken from her cell by the German Mattheus Schmitz and the Dutchman Maarten Kuijper, who was notorious for his cruelty, among other things. Fellow prisoners heard her screams. She was taken by car to Overveen. They stopped on a dirt road near the beach. Kuijper, Schmitz, and a Feldgendarme officer took her to the execution site. Schmitz walked behind her and fired a shot at her head, but the shot only wounded her. Kuijper then fired his machine gun until she fell dead. They hastily buried her in the dunes.

Resources and more information

Text on this page is largely taken from: Hannie Schaft The life story of a woman in resistance against the Nazis. (Erven Kors/Just Publishers BV, 2015)

Read more:

Sophie Poldermans: Hannie Schaft (pdf) – extended life story

Truus Menger-Oversteegen: Not Then, Not Now, Not Never.

Truus Oversteegen and her sister Freddie were in the resistance with Hannie Schaft as girls aged 16 and 14. In this book, Truus describes her memories of that period as if it happened yesterday.

How do you feel when you’re standing on the curb with your bike, waiting for the S.S. officer you’re supposed to shoot? Or when you’re ordered to lead a group of Jewish children to safety, but you fail? A compelling, personal account, suitable for ages 14 and up.

Buy Toen niet Nu niet Nooit van Truus Menger in onze webwinkel:

Khadija Arib, lezing 2016: ‘A free, inclusive, and just society is a great asset. We rarely consider how it came about, the struggles that led to it, or its core meaning.’

Job Cohen, lezing 2010: ‘Anyone who wants to sound the alarm, anyone who wants to warn of something big and terrible, shouldn’t join in this verbal onslaught. Let’s talk about everyday reality, not a tainted term like fascism, which is also interpreted in two or three ways.’

Sybrand Haersma Buma, lezing 2015: ‘In movies, war is a time of heroism. In reality, it’s a time that tears families, communities, and countries apart.’