Hannie Schaft, the girl with the red hair

For your speech or paper

At the end of World War II, the Nazis shot Hannie Schaft dead. They had long searched for this “girl with the red hair,” an active member of the resistance. She was the only woman reburied after the war at the Bloemendaal Cemetery of Honor. Books and a film were published about her life. She is still commemorated annually.

On this page, you can read more about Hannie Schaft’s life.

1920: Jannetje Johanna

Jannetje Johanna Schaft was born in Haarlem on September 16, 1920. Her nickname was Jopie or Jo.

Jo’s parents were socialist (left-wing). At dinner, they often discussed the news in the newspaper or on the radio.

When Jo was seven, her older sister Annie died of diphtheria, a contagious disease for which there was no vaccine at the time. Many children died from it. At that point, her parents only had Jo, and they were always afraid they would lose her too. Even in warm weather, Jo had to wear a cardigan, otherwise she might catch a cold. And she was always warned to be careful on the streets.

Tekening die Jopie Schaft maakte op de kleuterschool

School

Jo attended the Tetterode School, in her neighborhood, near Kleverpark in Haarlem. She was a good student and loved reading. She was shy and had no friends. According to her cousin, she was bullied because of her red hair and freckles. After primary school, she went to the HBS (similar to pre-university education) school. There, too, she had no friends. She didn’t participate in school parties or other activities. She was quiet, always focused on learning. Jo was determined to get the highest grade in the class, and she usually succeeded.

National socialism

In 1933, Hitler came to power. He transformed Germany into a dictatorship; he himself was the Führer (leader). Anyone who disagreed with him was imprisoned. Hitler and his followers (Nazis) hated Jews, Roma, people with disabilities, and homosexuals.

Jo Schaft’s family was very concerned, especially when the NSB gained many votes in the Netherlands. That party had similar ideas to Hitler’s party, the NSDAP.

Study

In 1938, Jo went to study international law in Amsterdam. She dreamed of later working for world peace in Geneva. This time, she did make friends and started going to parties. She befriended Philine Polak and Sonja Frenk, two Jewish students.

Hannie Schaft

When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Jo wanted to help. For months, she sent parcels to captured Polish officers through the Red Cross.

On May 15, 1940, the Netherlands was occupied. German soldiers marched through the streets. Yet, life went on. Jo had to study and graduated from the first part of her studies (bachelor’s exam) on July 1st. Together with her friends Annie and Nellie, she rented an attic room in Amsterdam. They listened to Radio Oranje—an illegal radio station—and sometimes took illegal pamphlets from the university. When German soldiers asked Jo for directions, she looked the other way. That was all she could do to resist during that period.

Persecution of Jews

In October 1940, everyone working for the government had to sign a declaration declaring themselves not Jewish. This was the Aryan Declaration. A month later, all Jews were dismissed. Several professors also disappeared from the university.

In February 1941, there was a major strike in protest against the arrest of four hundred Amsterdam Jews. Trains and buses stopped running, and businesses were shut down. This February strike was the first clear sign that many people were angry about the persecution of the Jews.

In the spring of 1942, all Jews were required to wear a star on their clothing. They were no longer allowed to cycle or travel by bus, tram, or train. And they were not allowed to be outside in the evenings and at night. Jo stole two identity cards (a kind of ID card) from the swimming pool locker room. She had them forged for her Jewish friends, Sonja and Philine. Shortly afterward, raids took place, and all the Jews were arrested. Jo helped her friends find hiding places just in time.

Council of Resistance

Jo wanted to make herself much more useful in the resistance. In the summer of 1943, she joined the Raad van Verzet (Resistance Council), a Haarlem resistance group. She became a courier: she transported illegal newspapers and weapons, relayed messages between various resistance groups, and guided people in hiding to safe houses. She also gathered intelligence about German defenses to pass on to England.

Jo becomes Hannie

Jo increasingly participated in resistance activities. This increased the risk of being recognized. So she dyed her red hair black and put on glasses. From then on, she was called Hannie. She slept in various hiding places. She had very little contact with her parents, lest she get them into trouble. One day, her parents were arrested. The Nazis hoped Hannie would then turn herself in. She almost did. But friends convinced her that the Nazis wouldn’t let her parents go even if Hannie turned herself in. After a few weeks, her parents were released.

Armed resistance

Hannie took shooting lessons. Along with other members of the group, she carried out attacks on at least eight Dutch people who collaborated with the occupiers.

These were police officers, members of the NSB (National Socialist Movement), or informers who betrayed many resistance fighters and Jews. Of course, they didn’t do such things lightly. It was the only way to prevent dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of people from being betrayed and killed by the occupiers. Once it was decided that someone had to be killed, they spied on them for days until they had determined the right time and place for the attack. Then two resistance fighters approached. One of them fired a shot and cycled away as quickly as possible. The other fired several more times. In one of these attacks, Jan Bonekamp was fatally wounded. He was a good friend of Hannie’s. After Jan’s death, she was depressed for a long time.

Stealing ammunition

Hannie often worked with sisters Freddy and Truus Oversteegen. On Christmas Eve 1944, they were ordered by the resistance in Velsen to remove five crates of ammunition from a submarine base in IJmuiden. On their hands and knees, they crawled a long way across the field to the base, while a searchlight swept overhead every minute. Then they returned the same way, carrying the heavy crates on their backs.

Not all attacks were successful. In early 1945, they attempted to blow up a railway bridge to prevent the transport of equipment to Germany. That attempt failed. An attack on an ammunition train was successful, disrupting traffic on that railway line for several weeks.

Arrested

On March 21, 1945—a month and a half before the end of the war—Hannie was arrested at a checkpoint. The soldiers had found illegal newspapers in her bicycle bag. They also found a pistol in her handbag. On their way to the prison in Amsterdam, someone recognized her as Hannie Schaft, the “rothaarige Mädel” (the girl with the red hair). They had been searching for her for a long time, as there had been numerous attacks in which witnesses had seen a “girl with red hair” cycling away quickly.

Hannie was placed in a cell by herself, far from the other prisoners. For over three weeks, she was interrogated day and night, barely able to sleep. Like many other “suspects,” she was given drugs to make her talk. She didn’t reveal much. After a while, she admitted to several attacks.

On April 17, 1945 – eighteen days before liberation – Hannie Schaft was taken to the dunes between Haarlem and Bloemendaal and shot dead. She was only 24 years old. After the war, mass graves were found in the dunes of hundreds of resistance fighters who had been executed there. 371 men, and Hannie Schaft, the only woman, were reburied at the Bloemendaal Cemetery of Honor.

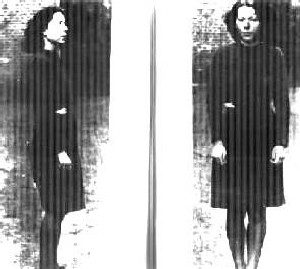

Hannie Schaft, shortly before the execution

Read more about women in the resistance

Truus Menger-Oversteegen: Toen niet Nu niet Nooit.

How do you feel when you’re standing with your bike in hand, waiting to see the SS officer you’re supposed to shoot? Or when you’re ordered to lead a group of Jewish children to safety, but fail?

Hannie Schaft often worked in the resistance with sisters Truus and Freddie Oversteegen. They were 16 and 14 when they joined. Truus Oversteegen later wrote down her memories of the war and the resistance. The way she tells it, it seems like it was only yesterday.

This book is suitable for readers aged 14 and up. It is available for purchase in the online store: